Ilene’s #oneword 2020 poster shows the word Community and some app logos like Flipgrid, Buncee, Wakelet

Over the past few years, I’ve participated in the #oneword movement. Each year since 2019, I have chosen a word after reflecting on the past year and my year ahead. As the year passes, I refer to my word and check in about how it resonates with me and relates to events in my life. For me, it’s a better guide than a New Year resolution and continues reverberating years later. I intentionally chose each #oneword to ensure they connect from year to year, which means they can be an even more powerful guide to me.

Here are my #onewords in yearly order:

2020: Transition

2021: Belonging

2022: Journey

2023: Bittersweet

2024: Bridge

I will share an example of how these words can be a powerful guide.

Since the early 2000s, I have passionately supported educators and education leaders with training, coaching, and mentoring. My work included attending and presenting at local, regional, and international conferences and providing these services to local Kuwaiti private schools through a consultancy I established in 2012. I attended and presented at conferences such as ISTE, ASCD, TESOL International, TESOL Arabia, INACOL, and BettMENA on various topics. It was something that was a part of my soul. I continued to do it even after I retired from full-time work as an administrator in 2019. It was a way to stay connected with people during the pandemic and stay busy in my retirement. I never thought I’d set this work aside. Until…

In Spring 2022, my son and daughter-in-law announced they were expecting a baby that Fall. A week or so later, my daughter and son-in-law announced they were expecting twins a few weeks before them. I was elated! I’d waited years to become a Nana, and now I would be a Nana three times! How awesome is that? Then reality set in. Both couples lived in different states on the Eastern coast of the U.S. at the time. I consulted with them and decided to travel from Kuwait to be with my daughter since she was due before my daughter-in-law. I also knew she would need help with the twins. When my daughter-in-law’s mother left to return to Kuwait in November, I arranged to spend time helping her and my son.

Fast forward to September 10, 2023, and the unexpected early birth of the twins by C-section. I immediately bought an air ticket to travel at the earliest available date. The babies were premature at 28 weeks, so they were hospitalized in the NICU for a month. My daughter was recovering from pre-eclampsia and the surgery, so she stayed in the hospital for a week. That gave me time to finish what I needed to do in Kuwait, pack, and head West. So began a year-long balance of life in the U.S. and Kuwait. All thoughts about my professional life were put on the back burner as I put systems in place to support my daughter and son-in-law as they navigated parenthood with two preemies. As I told them when I arrived, my goal was to support, not take over. They were going through a significant transition, and I was staying in their home. Decisions about what, how, and when to do things would come from them. Only when I was asked for suggestions would I make any. On the rare occasion when I felt strongly about something, I asked if I could give advice based on my experience. They appreciated that my role was supportive so they could set up a new life situation that worked for them. As a result, my relationship with them deepened.

However, I had to cancel 2023 conference appearances at ISTE, EDIT Summit, TESOL, and a local TESOL conference that I had committed to doing. As the year went on, I struggled every time I received a call for proposals from an organization I belonged to until I finally unsubscribed from most of them. In 2022 and 2023, I was focused on self-care (I’m not as young as I was when I had my kids, so taking care of babies with lots of needs at all times of day and night took a toll on me after a couple of months) and focused on my family. I was honest with my children and their spouses about making sure my health stayed a priority so I could keep helping them. That meant staying in the U.S. for a couple of months, then returning to Kuwait, where my husband awaited my short visits. Then, flying back to the U.S. to help out again. I did that five times in the space of ten months. I am privileged because I retired and have the time and financial means to do that.

It might surprise you that even after all this time and my devotion to my children and grandchildren, I struggled with giving up my passion for training and supporting teachers to have more time to focus on my family, especially my grandchildren. I also wanted to be available for my mother (she’s 99, reasonably self-sufficient, but needs me now and then). There was no time to work on presentations or submissions, and I had to withdraw from the conferences I’d already committed to. I have organized events and conferences, which creates more work for the organizers if someone changes their mind. That impacted me emotionally.

Now, back to my #oneword series.

In 2019, I transitioned from full-time work as a very involved administrator who worked long hours to retirement. Transition was a perfect word for that year as I navigated my life without a daily schedule.

In 2020, my #oneword was belonging. I focused on freelance consulting and presenting wherever and whenever I could. It helped my transition to retirement and supported my sense of belonging.

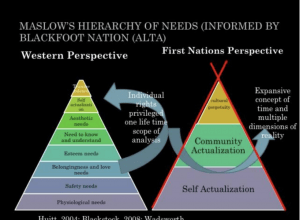

In 2021, advocate (verb and noun) was my #oneword. The world was still in the midst of the pandemic, and politics was dealing heavy blows to DEIJB initiatives. I grew up believing in people and their humanity. It was time for me to speak out about issues and listen to understand why, after many years of effort by people and organizations to bring equity and social justice to every individual, we were failing.

In 2022, my #oneword was journey. All of life is a journey, and I began to feel the need to view life in transition and my search for belonging as a path on my journey.

Last year, my #oneword was bittersweet. I felt the bittersweetness of leaving my freelance work (the bitter) and looking for other paths, like writing children’s books and spending time with my family (the sweetness), which was connected with belonging. I allowed myself to be available when my family needed me.

This year, I reflected on the past few years and looked forward. I realized that the year would still be a bit bitter with some sweetness and that I could be the bridge if I fully accepted the changes in my life. I also consider myself a bridge between people and cultures; people who’ve met me have mentioned the same. The main character of my first picture book is Aziza. She is a bi-racial Arab American living in Kuwait and navigating a world where difference makes it difficult for her to be included by her peers. Although she is bilingual (Arabic/English), she has a detectable accent when she speaks Arabic, and her classmates notice it. She is also much shorter than her peers, which makes her look younger than her age. I hope Aziza’s story will create a bridge between the perceptions of differences of her classmates and create a sense of belonging and community through their shared life experiences.

As you can see, I remain true to my passion: supporting children’s sense of belonging. Only this time, through storytelling, teachers can read to their students and discuss topics like inclusion and diversity. I’m also planning to write books for older children steeped in the history and culture of the Arabian Gulf region to broaden the perspective of readers from around the world.

My #oneword continues to guide my life. It’s only March, and I already see how “bridge” impacts my thinking about a future without conferences and consulting but filled with writing and imagining. It also pushes me to reach out virtually to the many educators I will no longer see in person. I want to keep those connections alive.