I have written several posts and an article about misunderstandings related to Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of needs including the pyramid that he never sketched. I have also mentioned the influence of his research, those of his contemporaries, and the indigenous teachings of the Blackfoot Confederation after Maslow spent the summer of 1938 with them doing fieldwork on his work that contributed to him modifying it over the years. I am now in the midst of editing my upcoming book about belonging and after posting my last article about the topic, I received comments from distinguished educators Ken Shelton and Barbara Bray that pushed me to dig deeper into the influence the Blackfoot teachings had on Maslow and his hierarchy of needs. I’m putting my findings into an order that makes sense to me and hopefully, my readers while giving credit to the experts who have thoroughly researched Maslow’s published and unpublished writing with a particular focus on the Blackfoot teachings. Today’s post is only a portion of what I’ve pieced together based on my searches.

Abraham Maslow is considered the founder of humanistic psychology that focuses on the whole person and includes self-efficacy, maximizing our potential (self-actualization) that leads us to wellbeing. Maslow’s hierarchy of needs is a motivational theory in psychology and comprises five tiers: the most basic human needs are physiological (food and clothing), then safety (job security), love and belonging needs (friendship), self-esteem, and self-actualization. The needs are explained in more detail in this article.

Those who took a course in psychology have probably learned about Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, but they might not be aware that Maslow did not visualize his theory of motivation as a pyramid. According to Scott Barry Kaufman, in his book, Transcend (2020), the pyramid and hierarchy of needs were created by a management consultant in the 1960s and became popular in organizational behavior courses at business schools. Since he didn’t create a pyramid, there is no basis to believe the Blackfoot tipi was turned upside down by Maslow.

In a recent interview by Scott Barry Kaufman in the journal, Scientific American, Todd Bridgman, Stephen Cummings, and John Ballard answer questions about the article they published in 2019 in the Academy of Management titled, “Who Built Maslow’s Pyramid: A History of the Creation of Management Studies’ Most Famous Symbol and the Implications for Management Education”. After a thorough search of Maslow’s writings and how Maslow’s theory appears in management textbooks, Bridgman, Cummings, and Ballard came to the conclusion that several management textbook authors during the 1950s and 1960s were responsible for a simplified version of Maslow’s theory and the creation of a pyramid to explain his theory to management students.

The pyramid isn’t the only misunderstanding or simplification of Maslow’s hierarchy. It is generally thought that Maslow believed the needs were linear and each had to be fully met before people could move on to the next. However, according to Maslow, “The human needs are arranged in an integrated hierarchy rather than dichotomously, that is, they rest one upon another. . . . This means that the process of regression to lower needs remains always as a possibility…” (Kaufman, p. xxviii)

Another misunderstanding about Maslow’s hierarchy of needs is how much influence his time with the Northern Blackfoot in Alberta, Canada had on his hierarchy. He spent the summer of 1938 with them as part of an anthropological study, and his field notes show his awareness of the differences between his upbringing and the one he observed. “Nearly all of the Blackfoot, he discovered, displayed a level of emotional security that only the upper percentiles of the U.S. population reached, and Maslow attributed this in large measure to the Indians’ emphasis on personal responsibility instilled from early childhood.” It seems that Maslow’s 1938 fieldwork research moved the direction of his interest to find the core of humanism, but his theory was also influenced afterward by leading psychologists of his time and his research. Therefore, we don’t really know what influences the Blackfoot society had on his work since there were so many other influences on him. We do know there should be more outward recognition of the Blackfoot influence and it should be explicitly stated.

Maslow “was concerned with creativity, freedom of expression, personal growth and fulfillment – issues that remain as relevant today in thinking about work, organizations, and our lives as they were in Maslow’s time. We think there’s an opportunity to create a new Maslow for management studies by returning to Maslow’s original ideas.” Maslow wondered, dreamed, and believed every person had the ability to reach self-actualization, but he searched all his life for what the motivation was. In fact, he became tired of average and believed all humans can reach self-actualization. Maslow believed we all have the potential to excel at our work whether we are talented musicians or menial laborers. “Maslow never proclaimed even the best people to be anything but human, susceptible to all-too-human flaws; but that did not mean he hoped for anything less than the remarkable for everyone. The essential question was not what made Beethoven Beethoven, but why everyone is not a Beethoven. Maslow was not his own dupe and knew well that musical or any other artistic genius is not bestowed equally, but he did hold that every person ought to be able to excel and find fulfillment in his work, whatever it was. Any work done with mastery possessed high dignity in his eyes.”

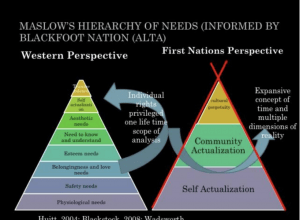

In 2007, Professor Terry Cross, a member of the Seneca Nation and founder of the National Indian Child Welfare Association (US) presented a keynote address, “Through Indigenous Eyes: Rethinking Theory and Practice”. He began the speech with an interpretation of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs in terms of indigenous culture and society and the different world views or collective thought processes of people (see graphic below from his PowerPoint slides)

Cross told the audience that the Western European and American worldview is linear while the native or tribal worldview is balanced and relational. In the Western worldview, time is linear. In the tribal or Native worldview, time is circular or cyclical. He also noted there are differences in each of the worldviews’ theory of change. For Westerners, change is the result of cause and effect while in the relational worldview “change is a constant, inevitable, cyclical, and dynamic part of the human experience that occurs in natural, predictable patterns and can be facilitated to promote desirable and measured outcomes.” (Cross, 2007) In 2011, Dr. Cindy Blackstock, a member of the Gitksan First Nation cites Cross’s work with worldview. In her article, “The Emergence of the Breath of Life Theory”, Blackstock “assumes that a set of interdependent principles known as the relational worldview principles (Cross, 2007) overlay an interconnected reality with expansive concepts of time and multiple dimensions of reality.” Although I haven’t studied earlier references to worldviews, I can see there is a focus on the needs of indigenous communities by researchers within those communities. There is a realization that in order to ensure the well-being of indigenous people, the lived experiences of those looking for solutions should have a similar worldview. In 2014, Karen Lincoln Michel attended a lecture by Dr. Blackstock where she referenced Maslow’s hierarchy of needs and the pyramid. She also bemoaned the lack of credit given to the Blackfoot by Maslow. It seems that until 2019, the pyramid was still associated with Maslow’s work.

Scott Barry Kaufman spent years researching Maslow’s work including unpublished letters and papers. In his book, Transcend (2020), Kaufman notes that Maslow understood there was no linear path to achieving self-actualization. His notes show his belief that people flow in and out of the different levels depending on their life circumstances and experiences. He also confirms that Maslow did not visualize his theory of motivation as a pyramid. It was indeed created by a management consultant in the 1960s.

After Blackstock’s essay was published in 2011, more people began writing about Maslow’s privileged use of Blackfoot teachings without giving them due credit. I have seen an awakening to the discussion, but I believe we’re missing an opportunity to focus on what we can learn from indigenous teachings instead of only criticizing Maslow for not recognizing where he may or may not have taken some of his ideas from and leaving the discussion at that point. I believe we can truly honor and recognize the indigenous teachings by learning about their worldview and their lived experiences.

There is so much to be learned from indigenous communities about living a fulfilling and satisfying life, but I will only touch on each one and provide references and videos for those interested in delving deeper.

The Emergence of the Breath of Life Theory (2011) by Dr. Cindy Blackstock

Breath of Life Theory: “(T)here are significant differences between First Nations* and western worldviews particularly in relation to time, interconnection of reality, and the First Nations belief that simple principles often explain complex phenomena such as the universe or humanity. The basic premise of the theory is that structural risks affecting children’s safety and well-being are alleviated when the relational worldview principles are in balance within the context and culture of the community.”

According to Native American child welfare expert Terry Cross in “the relational worldview model (Cross, 1997; Cross, 2007) the principles are categorized in four domains (cognitive, physical, spiritual, and emotional) of personal and collective well-being:

- COGNITIVE: self and community actualization, role, service, identity, and esteem

- PHYSICAL: water, food, housing, safety, and security

- SPIRITUAL: spirituality and life purpose

- EMOTIONAL: love, relationship, and belonging

The breath of life theory (BOL) predicts that, if the relational worldview principles are out of balance within the framework of community culture and context, then risks to the child’s safety and well-being will increase. BOL also suggests that child welfare interventions geared toward restoring balance among the relational worldview models principles will result in optimal safety and well-being for the community and their children.”

“Transformation Beyond Greed: Native Self Actualization” (2014) by Sidney Stone Brown

Sidney Stone Brown is a member of the Blackfeet Nation of Montana and currently the Behavioral Health Director of the Navajo Nation Department of Behavioral Health Services. Stone Brown notes in her address to the American Psychological Association in 2016 that “Foundational to Maslow’s hierarchy of needs theory is the idea – if we meet basic needs it will lead to peak experiences, authenticity, and dignity. So why don’t some individuals become actualized when their basic needs are met? This was a question Maslow searched for also. Stone Brown asks, “Could it be the insecurity of the society in which the individual lives?” Native Self Actualization occurs in a collectivist society while Western society is an individualist society.

Stone Brown was aware of Abraham Maslow’s view of self-actualization as a human need and the influence of his visit to the Blackfoot community in 1938. In fact, she requested access to all of his archives to ensure she was accurate in her portrayal of the work he did based on his visit. “When Maslow was on the Blackfoot (Siksika) Reserve in 1938, he learned from the young and old that giving back is not threatening to progress or wellbeing. Giving back protects the next generation. It prepares each person for their spiritual purpose and allows each person to become spiritually actualized. Peter Little Light, Blackfoot Medicine Man, would have spoken of these ways to Maslow, according to his step-grandson Clement Bear Chief, to convey to him the Blackfoot worldview. Maslow must have learned of the Blackfoot worldview about the purpose and meaning of life. And according to this worldview, becoming whole always involves service to others, putting others before ourselves.” (APA presentation. 2016)

Stone Brown’s work over the past twenty years includes creating and validating the Native Self Actualization Placement Assessment (NSPA). The NSPA is based on two major worldviews (traditional and contemporary) and is used for behavioral health services. Cultural worldviews represent the way a person views and relates to others. As she states in her speech to the APA in 2016, “Honoring all within the context of each person(s) unique mixture of traditional and contemporary skills allows each person to find their personal meaning for life.” You can find more information about Sidney Stone Brown, the NSPA, and her book on her website.

I will leave you with two final thoughts. First, from Kay Sidebottom:

“Why do we continue to ignore indigenous wisdom on which many of our educational theories rely? Along with the Blackfoot nation, which other thinkers are we failing to acknowledge in our teaching? What might happen if we begin to privilege other ways of knowing and being in the world? And – how can educators truly work to decolonise their curricula within neo-liberal systems which permeate and reinforce colonist practice? Taking a restorative approach requires us to explore these questions with humility, honesty and the willingness to confront our own role in the denial and promotion of colonialist practices. It asks us to be truth-seekers and to provide space for healing, for those who have been harmed by our systems.” (2019)

And finally, from Dr. Cindy Blackstock:

“It’s understanding one’s place in the world and acknowledging it. It’s realizing each day that I have been blessed with basic necessities and giving thanks for them. It’s doing my part to help my community and the greater good. Hopefully, these teachings practiced by my generation will inspire the next generation to take hold of them so they will endure.” (Blackstock, 2011)

*First Nation is a term used to identify Indigenous peoples of Canada who are neither Métis nor Inuit. This term came into common usage in the 1970s to replace the term “Indian” and “Indian band” which many find offensive.

References:

Cross, T.( 2007). https://www.snaicc.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/02242.pdf

Cross, T. https://youtu.be/LS8suhjvX4M

Kaufman, S. B. (2019,23 April). https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/beautiful-minds/who-created-maslows-iconic-pyramid

Michel, K. L. (2014). https://lincolnmichel.wordpress.com/2014/04/19/maslows-hierarchy-connected-to-blackfoot-beliefs

Sidebottom, K. (2019, 29 April). https://www.leedsbeckett.ac.uk/blogs/carnegie-education/2019/04/whose-knowledge/

Stone Brown, S. (2016). https://www.cdu.edu.au/sites/default/files/the-northern-institute/first_nations_symposium_-_27_sep_2019.pdf

Valiunis, A. (2011). https://www.thenewatlantis.com/publications/abraham-maslow-and-the-all-american-self