Today, I am featuring an article by Tara Brach in place of my weekly blog post. Tara outlines her interpretation of Buddhist practices that underline the need for self-belonging as the first step to wholeness and well-being. Her podcast is also a great resource for mindful practice and finding peace within ourselves.

(The following article originally appeared in the Spring 2001 issue of Inquiring Mind (vol. 17, number 2). www.inquiringmind.com

It’s here in all the pieces of my shame

That now I find myself again.

I yearn to belong to something, to be contained

In an all-embracing mind that sees me. . . .

-Rainer Maria Rilke

The intimacy that arises in listening and speaking truth is only possible if we can open to the vulnerability of our own hearts. Breathing in, contacting the life that is right here, is our first step. Once we have held ourselves with kindness, we can touch others in a vital and healing way. – Tara Brach

Our most fundamental sense of well-being is derived from the conscious experience of belonging. Relatedness is essential to survival. When we feel part of the whole, connected to our bodies, each other, and the living Earth, there is a sense of inherent rightness, of being wakeful and in love. The experience of universal belonging is at the heart of all mystical traditions. In realizing non-separation, we come home to our primordial and true nature.

The Buddha taught that suffering arises out of feeling separate. To the degree that we identify as a separate self, we have the feeling that something is wrong, something is missing. We want life to be different from the way it is. An acute sense of separation-living inside of a contracted and isolated self-amplifies feelings of vulnerability and fear, grasping and aversion. Feeling separate is an existential trance in which we have forgotten the wholeness of our being.

Never in the history of the world has the belief in a separate self been so exaggerated and prevalent as it is now in the twenty-first century in the West. In contrast to Asian and other traditional societies, our distinctive mode of identification is as individuals, without stable pre-existing contexts of belonging to families, communities, tribes or religious groups. Our desperate efforts to enhance and protect this fragile self have caused an unprecedented degree of severed belonging at all levels in our society. In our attempts to dominate the natural world, we have separated ourselves from the Earth. In our efforts to prove and defend ourselves, we have separated ourselves from each other. Managing life from our mental control towers, we have separated ourselves from our bodies and hearts.

With our Western experience of an extremely isolated self, we exemplify fully what the Buddha described as self-centered suffering. If we identify as a separate self, we become the background “owner” of whatever occurs. Ajahn Buddhadasa, a twentieth-century Thai meditation master, describes this conditioning to attach an idea of self to experience as “I-ing” and my-ing. Life happens emotions well up, sensations arise, events come and go and we then add onto the experiences that they are happening to me, because of me.

When inevitable pain arises, we take it personally. We are diagnosed with a disease or go through a divorce, and we perceive that we are the cause of unpleasantness (we’re deficient) or that we are the weak and vulnerable victim (still deficient). Since everything that happens reflects on me, when something seems wrong, the source of wrong is me. The defining characteristic of the trance of separation is this feeling and fearing of deficiency.

Both our upbringing and our culture provide the immediate breeding ground for this contemporary epidemic of feeling deficient and unworthy. Many of us have grown up with parents who gave us messages about where we fell short and how we should be different from the way we are. We were told to be special, to look a certain way, to act a certain way, to work harder, to win, to succeed, to make a difference, and not to be too demanding, shy or loud. An indirect but insidious message for many has been, “Don’t be needy.” Because our culture so values independence, self-reliance and strength, even the word needy evokes shame. To be considered as needy is utterly demeaning, contemptible. And yet, we all have needs-physical, sexual, emotional, spiritual. So the basic message is, “Your natural way of being is not okay; to be acceptable you must be different from the way you are.”

Almost two decades ago, author John Bradshaw and others enlarged our cultural self-awareness by calling attention to the crippling effect of shame. Since then, many have recognized the pervasive presence of shame much as we might an invisible toxin in the air we breathe. Feeling “not good enough” is that often unseen engine that drives our daily behavior and life choices. Fear of failure and rejection feeds addictive behavior. We become trapped in workaholism-an endless striving to accomplish-and we overconsume to numb the persistent presence of fear.

In the most fundamental way, the fear of deficiency prevents us from being intimate or at ease anywhere. Failure could be around any corner, so it is hard to lay down our hypervigilance and relax. Whether we fear being exposed as defective either to ourselves or to others, we carry the sense that if they knew . . . , they wouldn’t love us. A winning entry in a Washington Post T-shirt contest highlights the underlying assumption of personal deficiency that is so emblematic of our Western culture: “I have occasional delusions of adequacy.”

During high school, I consciously struggled with not liking myself, but during college I was distressed by the degree of self-aversion. On a weekend outing, a roommate described her inner process as “becoming her own best friend.” I broke down sobbing, overwhelmed at the degree to which I was unfriendly toward my life. My habit for years had been to be harsh and judgmental toward what I perceived as a clearly flawed self. My attachment to self-improvement transferred itself into the domain of spiritual practice. While I realized at the time that kindness was intrinsic to the spiritual path, in retrospect it is clear how feeling unworthy directly shaped my approach to spiritual life.

I moved into an ashram and spent twelve years trying to be more pure-waking up early, doing hours of yoga and meditation, organizing my life around service and community. I had some idea that if I really applied myself, it would take eight or ten years to awaken spiritually. The activities were wholesome, but I was still aiming to upgrade a flagging self. Periodically I would go to see a spiritual teacher I admired and inquire, “So, how am I doing? What else can I do?” Invariably these different teachers responded, “Just relax.” I wasn’t sure what they meant, but I didn’t think they really meant “relax.” How could they? I clearly wasn’t “there” yet.

During a six-week Buddhist meditation retreat, I spent at least twelve days with a stomach virus. Not only was there physical discomfort, but I found that I made myself “wrong” for being sick. Having already struggled with chronic sickness, this retreat made it clear just how harshly I had been relating to myself. Sickness had become another sign of personal deficiency. My assumption was that I didn’t know how to take care of myself. I feared that being sick reflected unworthiness and a basic lack of spiritual maturity.

In one of the evening dharma talks, a teacher said, “The boundary to what we can accept is the boundary to our freedom.” For me this rang incredibly true. I had been hitting that boundary repeatedly, contracted by the almost invisible tendency to believe something was wrong with me. Wrong if I was fatigued, wrong if my mind was wandering, wrong if I was anxious, wrong if I was depressed. The overlay of shame converted unpleasant experiences into a verdict on self. Pain turned into suffering. In the moment that I made myself wrong, the world got small and tight. I was in the trance of unworthiness.

Several years ago, at a meeting with a group of Western teachers, the Dalai Lama expressed astonishment at the degree of self-aversion and feelings of unworthiness reported by Western students. I know many friends and students who have found, as I did, that even after decades of spiritual practice, they are still painfully burdened by feelings of personal deficiency. Many assumed that meditation alone would take care of it. Instead, they found that deep pockets of shame and self-aversion had a stubborn way of persisting over the years.

Carl Jung describes a paradigm shift in understanding the spiritual path: Rather than climbing up a ladder seeking perfection, we are unfolding into wholeness. We are not trying to transcend or vanquish the difficult energies that we consider wrong-the fear, shame, jealousy, anger. This only creates a shadow that fuels our sense of deficiency. Rather, we are learning to turn around and embrace life in all its realness-broken, messy, vivid, alive.

Yet even when our intention in spiritual practice is to include the difficult energies, we still have strong conditioning to resist their pain. The experience of shame-feeling fundamentally deficient-is so excruciating that we will do whatever we can to avoid it. The etymology of the word shame is “to cover.” Rather than feel the rawness of shame, we develop life strategies to cover and compensate for its presence. We stay physically busy and mentally preoccupied, absorbed in endless self-improvement projects. We numb ourselves with food and other substances. We try to control and change ourselves with self-judgment or relieve insecurity by blaming others. We are so sufficiently defended that we can spend years meditating and never really include in awareness the feared and rejected parts of our experience.

Often those who feel plagued by not being good enough are drawn to idealistic cosmologies that highlight the sense of personal deficiency but offer the possibility of becoming a dramatically different person. The quest for perfection is based on the assumption that we are faulty and must purify and transcend our lower nature. This perception of spiritual hierarchy, of progressing from a lower to a higher self, can be found in elements of most Western and Eastern religions.

When we are in the process of trying to ascend, we never arrive and always feel spiritually insufficient. This was clearly the case during my first years of practice in pursuit of becoming a more perfect yogi. The temporary and passing states of peace or rapture were never enough to soothe my underlying sense of unworthiness. I felt continuously compelled to do more. An alternative face of such insecurity is spiritual pride. The very accomplishments-like improved concentration or periods of bliss-if owned by the self, reinforce a sense of a deficient self that is moving up the ladder. With either pride or shame, our awareness is identified as an entity that is separate and afraid of failure.

In my own unfolding, as well as with friends, clients and dharma students, an intentional spotlight on shame and unworthiness has been enormously revealing. Many people have told me that when they realize how pervasive their self-aversion is and how long their life has been imprisoned by shame, it brings up a sense of grief as well as life-giving hope. Fear of deficiency is a prison that prevents us from belonging to our world. Healing and freedom become possible as we include the shadow-the unwanted, unseen and unfelt parts of our being-in a wakeful and compassionate awareness.

* * *

For a child to feel belonging, he or she needs to feel understood and loved. We each feel a fundamental sense of connectedness when we are seen and when what is seen is held in love. We habitually relate to our inner life in the same way that others attended to us. When our parents (and the larger culture) don’t respond to our fears, are too preoccupied to really listen to our needs or send messages that we are falling short, we then adopt similar ways of relating to our own being. We disconnect and banish parts of our inner life.

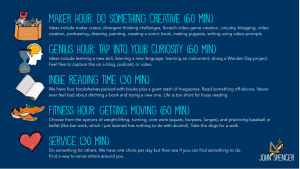

Meditation practices are a form of spiritual reparenting. We are transforming these deeply rooted patterns of inner relating by learning to bring mindfulness and compassion to our life. An open and accepting attention is radical because it flies in the face of our conditioning to assess what is happening as wrong. We are deconditioning the habit of turning against ourselves, discovering that in this moment’s experience nothing is missing or wrong.

The trance of unworthiness, sustained by the movement of blaming, striving and self-numbing, begins to lift when we stop the action. The Buddha engaged in his mythic process of awakening after coming to rest under the bodhi tree. We start to cut through the trance in the moment that we, like the Buddha, discontinue our activity and pay attention. Our willingness to stop and look-what I call the sacred art of pausing-is at the center of all spiritual practice. Because we get so lost in our fear-driven busyness, we need to pause frequently.

The Buddha realized his natural wisdom and compassion through a night-long encounter with the forces of greed, hatred and delusion. We face the shadow deities by pausing and attending to whatever presents itself-judgment, depression, anxiety, obsessive thinking, compulsive behavior. Because shame and fear often are not fully conscious, we can deepen this attention by inquiring into what is happening. Caring self-inquiry invites the habitually hidden parts of our being into awareness.

If I pause in the midst of feeling even mildly anxious or depressed and ask, “What am I believing?” I usually discover an assumption that I am falling short or about to fail in some way. The emotions around this belief become more conscious as I further inquire, “What wants attention or acceptance in this moment?” Frequently I find contractions of fear under the story of insufficiency. I find that the trance is sustained only when I reject or resist experience. As I recognize the mental story and open directly to the bodily sense of fear, the trance of unworthiness begins to dissolve.

There are times that the grip of fear and shame is overt and vicelike. At a retreat I led a few years ago a young man named Ron came into an interview with me and announced that he was the most judgmental person in the world. He went on to prove his point, describing how scathing he was toward his every thought, mood and behavior. When he felt back pain, he concluded that he was an “out of shape couch potato, not fit for a zafu.” When his mind wandered, he concluded he was hopeless as a meditator. During the lovingkindness meditation, he was disgusted to find that his heart felt like a cold stone. In approaching an interview with me, he felt caught in the clutch of fear, embarrassed that he would be wasting my time. While others were not exempt, his most constant barrage of hostility was directed at himself. I asked him if he knew how long he had been turning so harshly on himself. He paused for quite a while, his eyes welling up with tears. It was for as long as he could remember. He had joined in with his mother, relentlessly badgering himself and turning away from the hurt in his heart.

The recognition of how many moments of his life had been lost to self-hatred brought up a deep sorrow. I invited him to sense where his body felt the most pain and vulnerability. He pointed to his heart, and I asked him how he felt toward his hurting heart at that moment. “Sad,” he responded, “and very sorry.” I encouraged him to communicate that to his inner life-to put his hand on his heart and send the message, “I care about this suffering.” As he did so, Ron began to weep deeply.

In Buddhist meditation, a traditional compassion practice is to see suffering and offer our prayer of care. Thich Nhat Hanh suggests that when we are with someone who is in pain, we might offer this deeply healing message: “Darling, I care about your suffering.” We rarely offer this care or tenderness to ourselves. We are definitely not used to touching ourselves, bringing the same tenderness that we might to stroking the cheek of a sleeping child, and gently placing a hand on our own cheek or heart. For the remaining days of the retreat, this was Ron’s practice. When he became aware of judging, he would consciously feel the vulnerability in his body-the place that for so long had felt pushed away, frightened, rejected. With a very gentle touch, he would place his hand on his heart and send the prayer of care. Ron was sitting in the front of the meditation hall, and I noticed that his hand was almost always resting on his heart.

When we met before the closing of the retreat, Ron’s whole countenance was transformed. His edges had softened, his body was relaxed, his eyes were bright. Rather than feeling embarrassed, he seemed glad to see me. He said that the judgments had been persistent but not so brutal. By feeling the woundedness and offering care, he had opened out of the rigid roles of judge and accused. He went on to tell me something that had touched him deeply. When he had been walking in the woods, he passed a woman who was standing still and crying quietly. He stopped several minutes later down the trail and could feel his heart hold and care for her sadness. Self-hatred had walled him off from his world. The experience of connection and caring for another was the blessing of a heart that was opening.

The Buddha said that our fear is great, but greater yet is the truth of our connectedness. Whereas Ron was able to rediscover connection and loosen the trance of unworthiness by tenderly offering kindness to his wounds, we might feel too small, too tight and aversive to open to the pain that is moving through us. At these times it helps to reach out, to discover an enlarged belonging through our friends, sangha, family and the living Earth. A man approached the Dalai Lama and asked him how to deal with the enormous fear he was feeling. The Dalai Lama responded that he should imagine he was in the lap of the Buddha.

Any pathway toward remembering our belonging to this world alleviates the trance of separation and unworthiness. After his night under the bodhi tree, the Buddha was very awake but not fully liberated. Mara had retreated but not vanished. With his right hand, the Buddha touched the ground and called on the Earth goddess to bear witness. By reaching out and honoring his connectedness to all life, his belonging to the web of life, the Buddha realized the fullness of freedom.

We are not walking this path alone, building spiritual muscles, climbing the ladder to become more perfect. Rather, we are discovering the truth of our relatedness through belonging to these bodies and emotions, to each other, and to this whole natural world. As we realize our belonging, the trance of unworthiness dissolves. In its place is not worthiness; that is another assessment of self. Rather, we are no longer compelled to blame or hide or fix our being. When we turn and embrace what has felt so personal, we awaken from feelings of separateness and find that we are in love with all of life.

The link to this article: https://www.tarabrach.com/articles-interviews/inquiring-trance

Tara Brach is a teacher and founder of the Insight Meditation Community of Washington, D.C.,and teaches throughout the United States and Europe. She is a clinical psychologist and author of Radical Acceptance: Embracing Your Life with the Heart of a Buddha,True Refuge: Finding Peace and Freedom in Your Own Awakened Heart, and Radical Compassion: Learning to Love Yourself and Your World with the Practice of R.A.I.N.

More resources about self-belonging including Tara’s article can be found on my website.